From the archive: Cecil Beaton's Redditch House (1962)

The visitor comes upon Redditch House so unexpectedly, even after directions from a villager, that first appraisal of the small, grand façade can easily be scamped. Yet that would be a pity, for there it is, handsome as an elevation for a Whig palace, but all scaled down so that the visual impact is one of charm with nothing of pretension. Weathered stone pilasters and ancient brick combine in an unusually harmonious contrast of texture and colour.

The entrance hall is a study in a rare kind of grandeur in miniature, little seen in England at any time, but frequently to be found in the villas of the Italian Renaissance. Working with Felix Harbord, Mr Beaton transformed three or four cubby-holes into a stone-flagged, scagliola-columned hall which is probably no more than fifteen feet square. The spring-board to the notion was an oak beam on which the whole house virtually rests. That beam is now boxed and frames one of the compartments of the ceiling. Nothing is central, all is symmetry and all is minuscule splendour.

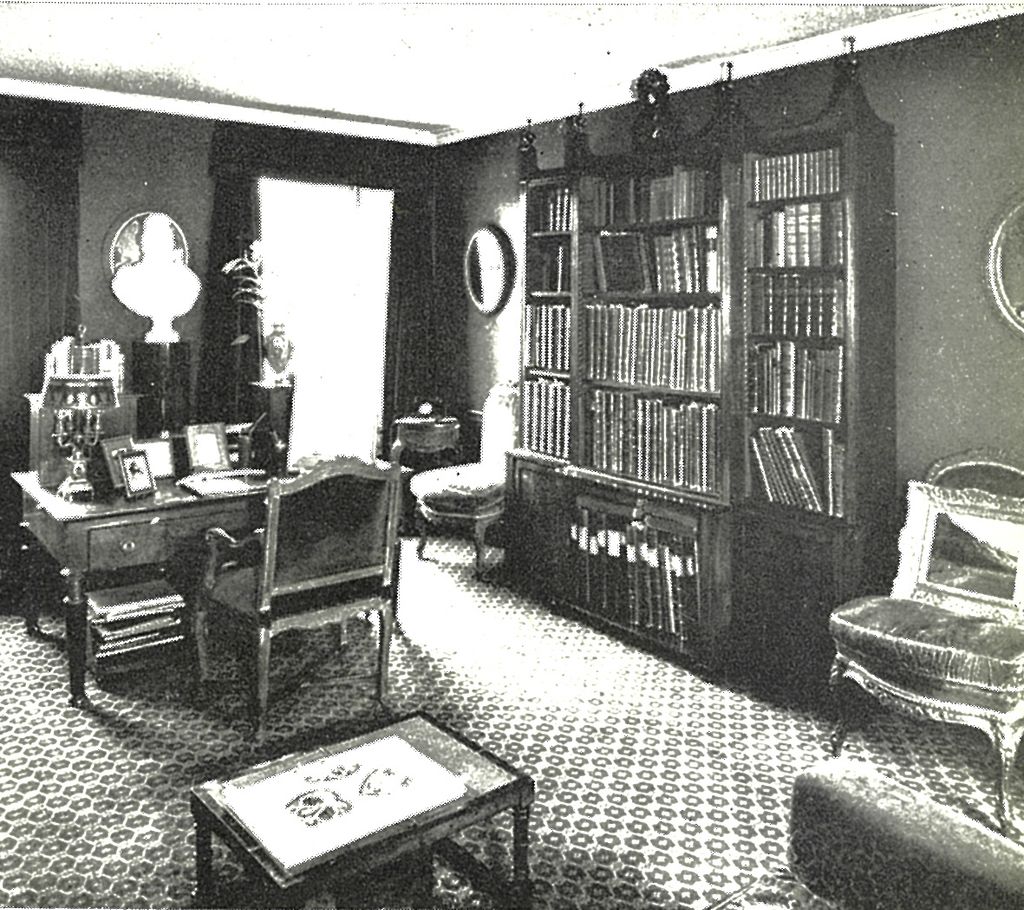

Opening off the hall is a room which is part workroom, part winter sitting-room, thanks to central heating and double-glazing. This room is furnished somewhat austerely and is dominated by three pieces: an enormous sofa, a high breakfront bookcase with fine finials, and a writing table which formerly belonged to Lady Juliet Duff and once upon a time reputedly was Talleyrand's. It is a four-square, handsome, masculine piece in fruitwood and might well be conducive to the penning of historic aide-memoire.

One of the major charms of Redditch House is its accidental multi-level living, which could well prove the envy and despair of any modern architect with a mania for split-level planning. Mr Beaton's dining-room (constructed from the old kitchen), with its Roman marble table-top under a boldly barrel-vaulted ceiling, is down a few steps. So, too, is the flower room. The drawing-room, on the other hand, is up a few steps, as are a guest's bedroom and the garden room.

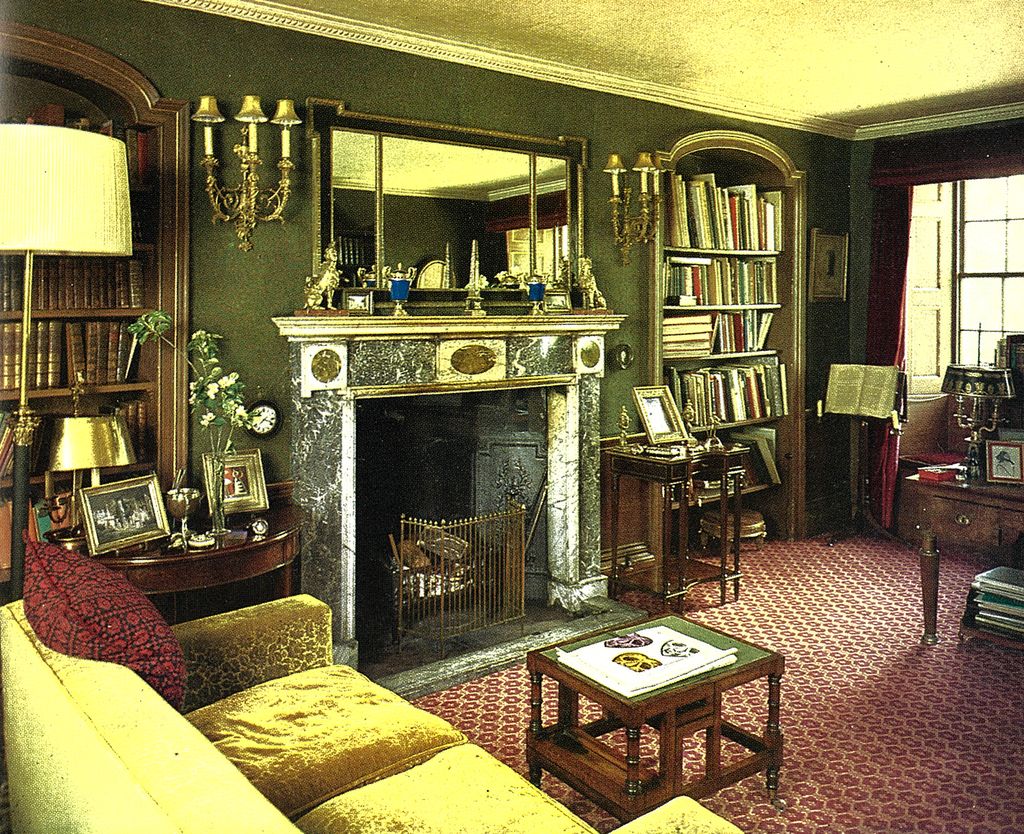

There are scores of decorative ideas in this house, but the drawing-room presents the most formidable assembly of Mr Beaton's triumphs over some pretty formidable odds. When he first came to Broad Chalke the drawing-room was a square room of no especial merit. This room is the ground floor of the building of later date which can be seen in the photograph. This wing is set at right angles to the main structure of the house. Mr Harbord had the idea of extending this part of the house, inserting another window and hipping the roof. This bold scheme gave Mr Beaton a drawing-room of some thirty-five feet in length, but, as the ceiling remains at its original height of nine feet or so, the result is that most covetable of all room shapes: a grand room which invites and never intimidates. To introduce a pair of chandeliers into such a room might seem, to the faint-hearted, a dangerous decorative touch, but there they are, so far unscathed, and with the brows of Mr Beaton's taller guests equally free from wounds. This room has one enormous sofa and two fireside sofas of such precisely curved forms that only the most demure of visitors would be likely to take their places thereon. For others, that large sofa is plainly the place.

When this room was extended, the opportunity was taken of curving the new interior wall on either side of the new end window and inserting a pair of large round-headed niches which now house a pair of enormous Meissen porcelain jars. Almost within the bow thus formed stands a splendid inlaid tall Louis XVI desk with ormolu mounts, secret drawers which contain an amusing assembly of caricatures of friends, and on top, a Rex Whistler design for a needlework rug worked by Mr Beaton's mother. The walls of this room are crowded with a personal collection of paintings which owe nothing to fashionable foibles and market values. A painting by Rex Whistler of Mr Beaton's earlier home at Ashcombe, high on the Wiltshire downs; a Tchelitchew; studies by a pupil of James Thornhill; Victorian flower paintings; a nocturne by Le Sidaner; an eighteenth-century portrait of General Wolfe; a Graham Sutherland design for a needlework cushion, and a dozen other paintings glow from the deep wine-red walls of this room.

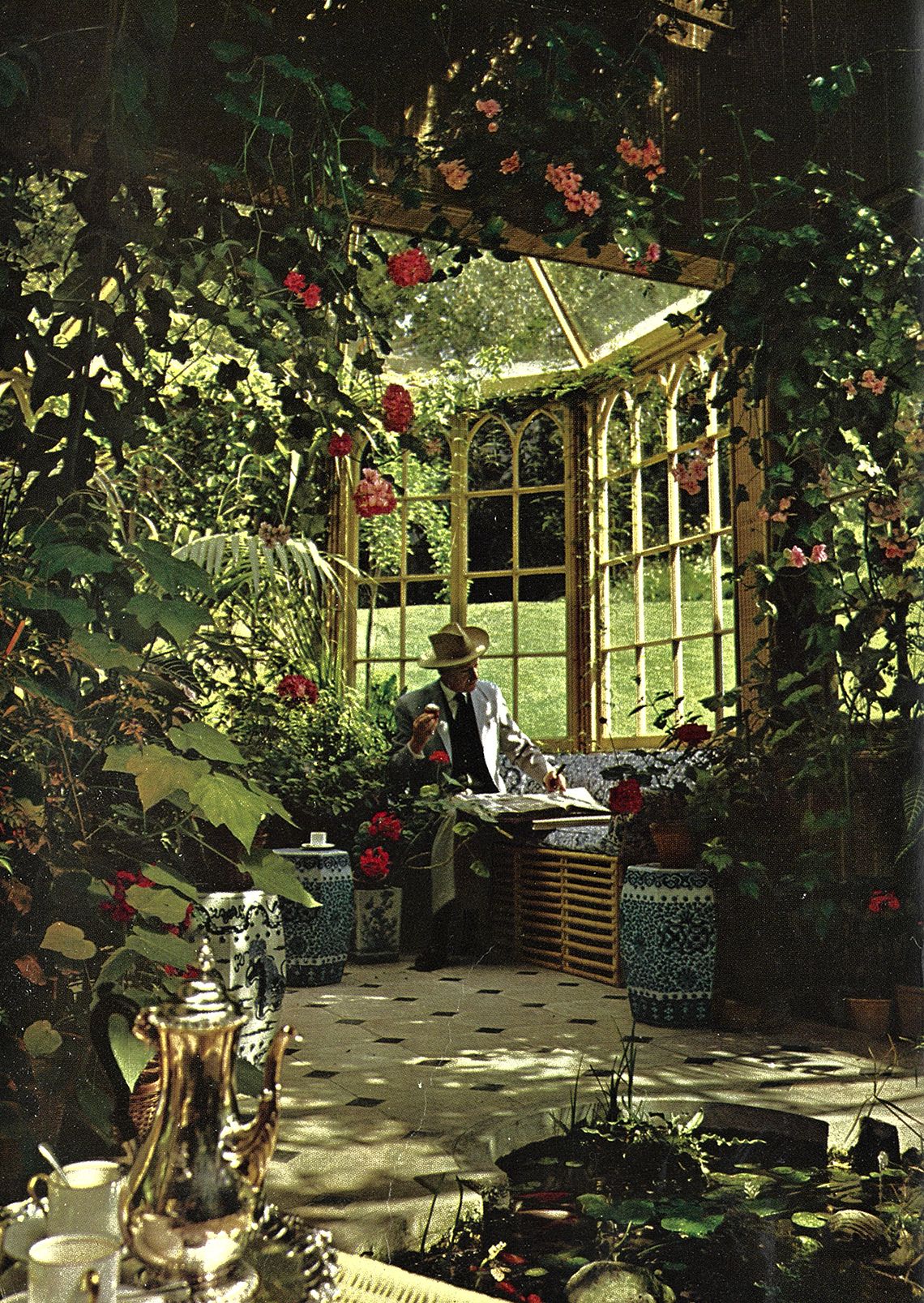

But the greatest boon derived from Mr Harbord's extension of the wing, says Mr Beaton, was the conservatory, and many weekend visitors who have been given the blue-and-white bedroom which opens into this garden room would be likely to agree with him. This quiet retreat, which also adjoins both garden and drawing-room, is as tranquil as any monastery garden tucked away on San Francesco del Deserto. Only the gentle fall of the water from the low fountain into the goldfish pool stabs at the silence of the nearby Downs. The visitor reclines in a wickerwork rocking-chair from a porch in the American Deep South, feeling like an Edwardian politico remaking yet another Anglo-French agreement defining yet more spheres of influence.

MAY WE SUGGEST: The Wiltshire manor house of a lover of the early eighteenth century

And beyond is the garden with its bold turfed slopes, leading up to the woodland ridge with its majestic beeches, oaks and sycamore trees. Nearer are the gravelled walks and that sheltered, stone-flagged, balustraded sun-trap in the corner formed by the linking of the old house and the later wing, a corner made for tea and conversation. This, confesses Mr Beaton, is the bit of Redditch he most nostalgically remembered when working on drawings for Gigi in a bungalow in the grounds of the Beverly Hills Hotel; which is, he hastens to add, a very comfortable home from home, but a far, far cry from Broad Chalke, Wiltshire.

Little space remains to mention the garden, or rather gardens, which Mr Beaton has made at Redditch, and which are as prolific in ideas as the house itself: the recently made rose garden, for instance, with its grass paths and centred armillary sphere; the small greenhouse with its climbing rose which flowers in March; the Wiltshire walls with their thatched capping ... and so on and so on. These must be left for another article.