The sweet, earthy aroma of crushed apples fills the autumn air as centuries of cyder making traditions come alive in Somerset at this time of year. I’ve made a trip to Hadspen House, outside Bruton, a grand Georgian manor built of local burnt-orange limestone, the seat of the Hobhouse family since 1785 and occupied by generations of Hobhouse gentry, politicians and finally renowned garden designer Penelope Hobhouse. Bought by Koos Bekker and Karen Roos in 2013 Hadspen was transformed into The Newt: a boutique hotel, a luxury country estate with cyder orchards, a working farm and multiple restaurants for day and overnight guests to experience. The acquisition of an old property by wealthy new custodians is nothing new but the reimagining of this beautiful corner of Somerset by Becker and Roos is unique in its sensitivity to the environment and a re-anchoring this historic site to a new chapter. Somerset is cyder country and apple trees are the roots they chose to lay down.

Cyder making has deep, time-honoured traditions in the west country where it has long been part of the agricultural calendar and social life. The early autumn apple harvest would be a chance for communities to gather to help in the process, pressing for neighbours and sharing the yield. Traditionally, apples were crushed in a stone mill then pressed between layers of straw, the juice running into barrels or tubs and left to ferment. The process could take weeks to months depending on the temperature, and once fermentation slowed, barrels were ‘racked off’ to remove sediment then left to mature until spring or summer before being drunk.

Apple trees are woven into the fabric of the English landscape, as familiar as church towers or berry dotted hedgerows, and for centuries apple trees have marked the rhythm of the seasons from blossom to harvest. Sheep grazing under the trees in spring is a form of silva culture that new generation farmers are reinstating today.

Like any living thing apple trees are affected by the seasonal weather changes, some years, like this, there will be a mast crop and a hot summer will ensure the vital sugar content which produces fermentation. Industrially produced cyder will use concentrate that ensures a consistency of product with added water to stretch it further.

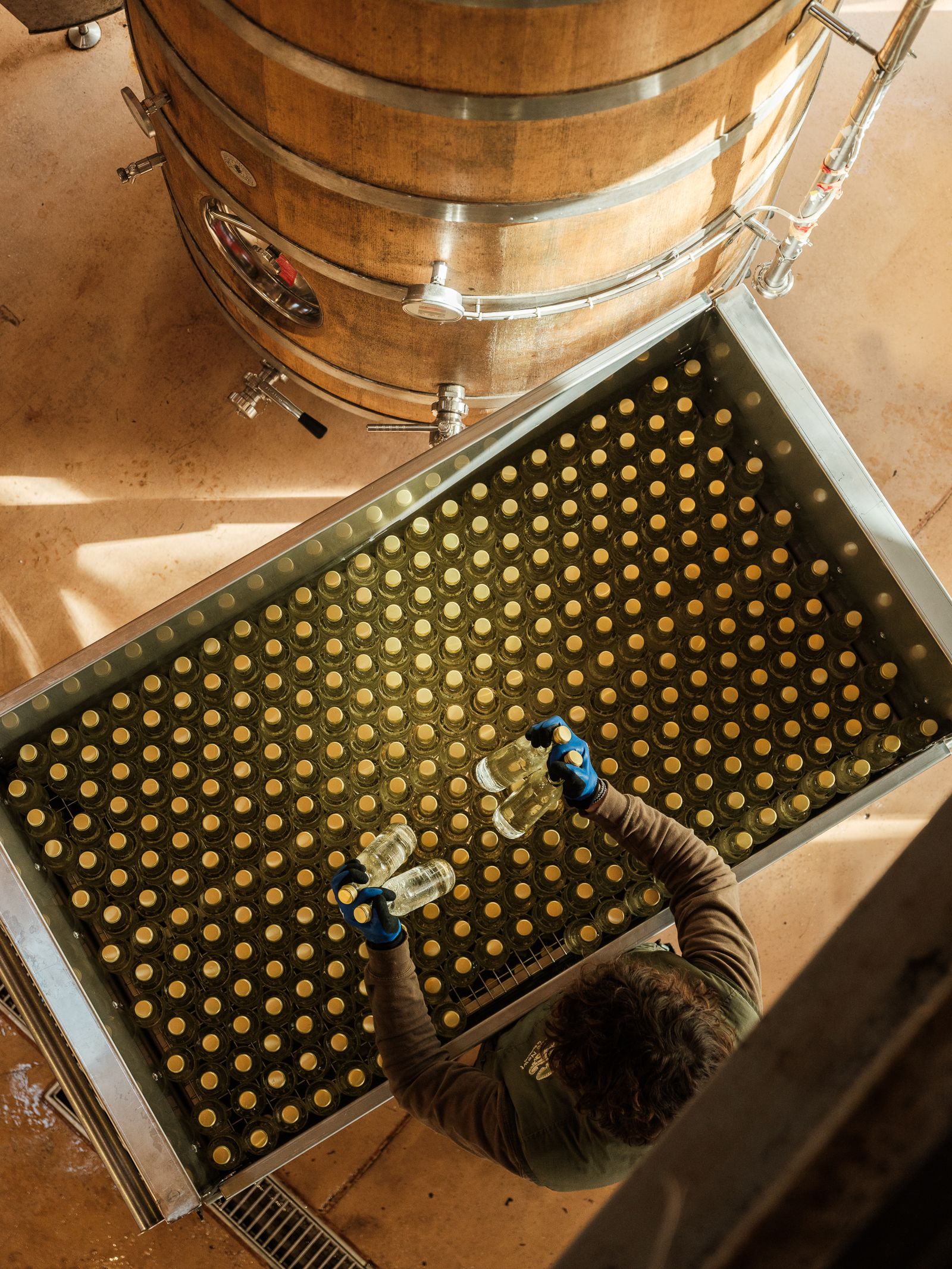

At the Newt they offer a ‘cyder’ experience, albeit in fast forward - it lasts a few hours rather than back breaking days, and includes tours exploring the orchards, where guests can learn about heritage apple varieties, to the magnificently restored barns that house a cyder press and cellar for tastings and and a hands-on cyder-making workshop where you can press apples, start the cyder-making process, and take home a demi-john of your own.

Acres of The Newt’s estate have been planted as orchards and we wander amongst aptronymously named Never Blight, Filbarrel and Morgans sweet apple trees filling buckets to press and bottle. Sampling our choices, I’m interested to discover the spectacular range of flavour and characteristics each has: sweetness, fragrance and some with acidity and tannins to balance the effect - I’m using my palate in the same way I would to taste wine.

The process hasn’t changed much but the equipment has and their state of the art machinery fires into action while the stone mill and presses sit unused at the other side of the courtyard as historic memorabilia.

After our relatively hands on approach we choose to allow the wild yeasts to ferment our juice - similar to the concept of a sourdough starter, these are invisible and airborne. Others in the group choose to kill the existing bacteria and reintroduce a man made yeast.

Wild fermentation is risky but is at the heart of traditional cyder making, profoundly affecting the flavour and character of cyder, giving it a sense of place or terroir, achieving natural layered aromas and a balance of tannins, acids and sweetness. Commercial producers would add their own yeast (and more of it) for both control and to increase the speed of fermentation. Slower fermentation gives a softer, more rounded texture.

Cyder is making a serious comeback with many small artisan producers and restaurants listing it on their menus. It’s come a long way from the rough farm labourers' drink and sweet commercial brands, yet it remains a cornerstone of British rural life and history, a celebration of old ways in a modern world, of maintaining tradition and ritual, respecting the natural processes and the beauty of nature. Nothing is so perfectly at home as something that has been there forever and the new custodians of Hadspen and its estate have found this story to tell.