Our travel editor's love letter to the hilltop towns of Basilicata

As I arrived in Matera, the day had already started its descent into darkness, swallowing the honeycomb caves of the Sassi under its golden light as swirls of black starlings danced across the dusk sky. A limestone gorge encircles this ancient hilltop city and, with the river Gravina cutting between them, it appeared as if the earth had turned inside out. Hundreds of caves flecked the steep rock face, their hollowed entrances peering out of the craggy landscape like black holes luring you in.

Matera is among hundreds of time-locked towns in the isolated and barren Basilicata region of Southern Italy, which stretches between the green Dolomiti Lucane mountains and the Ionian Sea. Its beauty cannot be defined by a single monument or building, but rather by the sum of its parts.

When you walk through the beguiling cobbled lanes, it is hard to imagine its deterioration from one of Europe's first settlements in the Paleolithic period to a source of national shame by the 20th century. In the 1950s, its residents were relocated from the caves into new housing surrounding the Sassi (which means stones) for sanitary conditions, having previously lived without plumbing or electricity, alongside their livestock. By the 1980s, Matera had been completely abandoned, as Basilicata underwent industrialisation.

In an unlikely tale of reinvention, a visit today reveals not a place of shame, but a source of great pride. Matera has been resurrected, as hotels, restaurants and shops thrive thanks to tourism and locals are returning to the place of their ancestors. Under Unesco protection since the 1990s, its 13th-century rock churches and palazzos have been slowly unearthed, drawing visitors from across the world with their esoteric wonder. In 2019, Matera was named the European Capital of Culture, placing it firmly on the map before it was featured in the James Bond film No Time To Die in 2021.

It takes a certain sensibility to recognise the potential in the proletarian. Daniele Kihlgren, a Swedish-Italian thinker and son of a cement magnate, is perhaps an unlikely saviour. But he has rebelliously dedicated himself, through his organisation Sextantio, to rescuing the forgotten villages of Southern Italy - protecting them from the brutalities of time and from 'contamination by ugly new cement constructions'.

'Italians have a good school of restoration, but at the same time, it's ideological,' he says. "To be preserved, historical sites have to be something important, like that of the glory of the Roman Empire or the Renaissance - but not this sort of poor historical heritage.' His hope is to create an economic model that could save thousands of settlements and provide a return for their inhabitants, without compromising their identity - which is at once most vulnerable and most valuable.

He chanced upon what would become his first restoration project during a motorcycle ride in 1999, finding the town of Santo Stefano di Sessanio in the Abruzzo region of the south. Here, he has created an albergo diffuso (scattered hotel) with rooms and taverns spread across the town, working with the few remaining locals, as well as archaeologists and engineers, to restore about 70 per cent of its footprint.

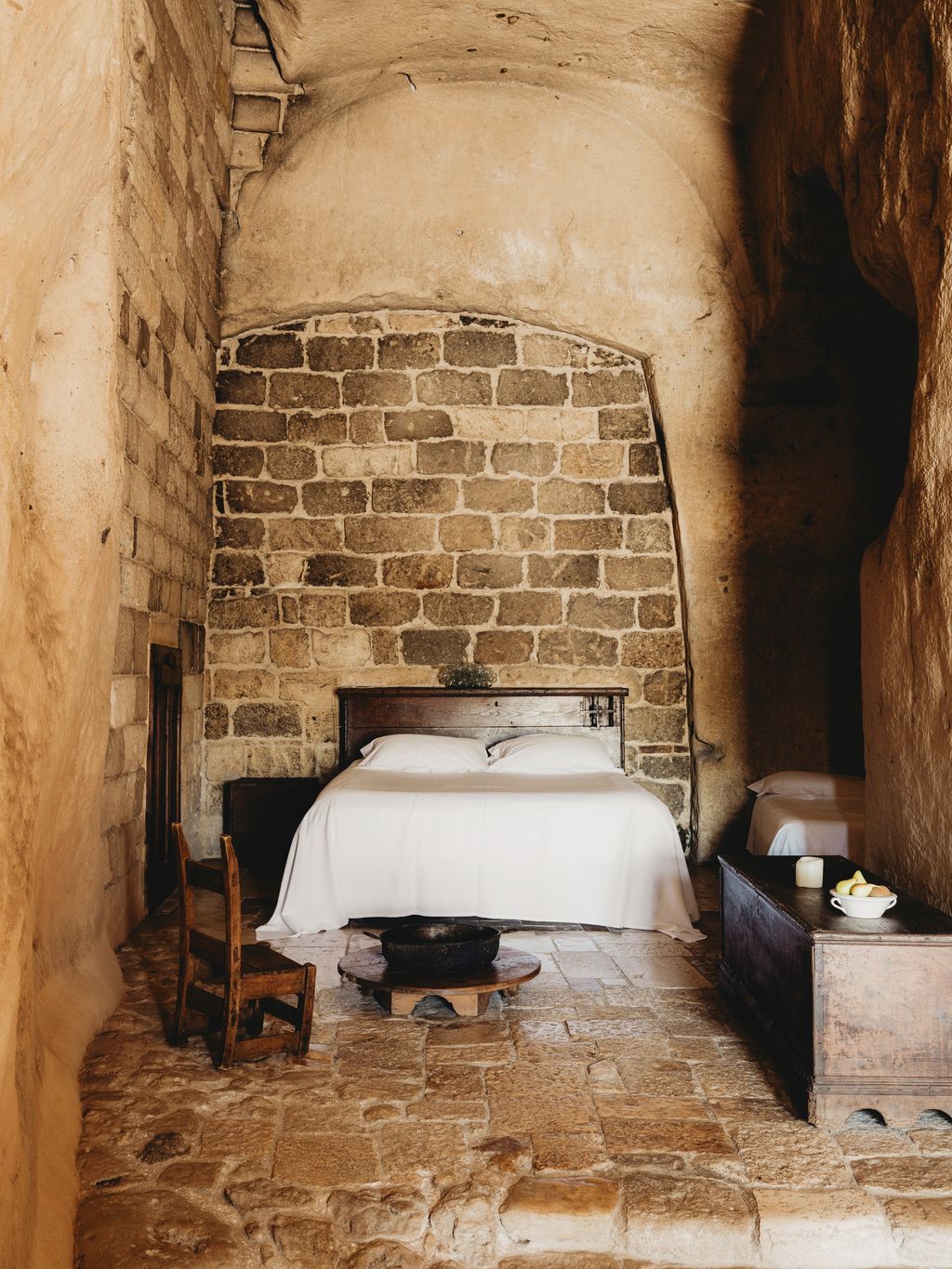

In Matera, he has restored caves up and down the hillside creating 18 magical rooms and a dining area in a 13th-century church, which has sweeping views over the gorge of Murgia. His latest project was the restoration of the Palazzo de Civita last summer, carving five further places to stay under Sextantio Le Grotte della Civita. 'When I arrived in the caves, I found only mattresses and syringes - it was wasted land,' he says. ‘But, to me, the idea was simple: to preserve the integrity of this ancient place so it can be given to the next generation.’

The dwellings and the landscape have always existed as one in Matera: in caves, a home is not defined by four walls; the walls are defined by nature. In keeping with this, the original cave walls and windows dictated the configuration of rooms during the restoration. Interiors are minimally dressed with wooden furniture found locally in abandoned houses, or otherwise reproduced with historical accuracy. Candles lead you through the vaulted spaces, lighting beds in crisp white linen and freestanding baths on the original rock (now with underfloor heating). Walls retain their marks and stains, be it from past fires, cisterns that once collected rainwater below ground, or the accidents of life.

Days are spent climbing the ravine of Murgia Materana Park - covered in 1,200 rare species of flora and fauna - past meandering streams and into the 150 remaining rock churches as birds of prey soar above. From Matera, a day trip to the ghost town of Craco reveals another of Basilicata's mysterious beauties. Having first been inhabited by the Ancient Greeks around 540 BCE and left abandoned since the last century due to faulty pipework thought to have caused a landslide, it is another enchanting James Bond film location in Quantum of Solace, as well as Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ.

An hour's drive inland and up the Dolomiti Lucane, the towns of Castelmezzano and Pietrapertosa seem to dangle in the air amid mountain peaks. The peasant path of the Seven Stones is a scenic hike between the two, or in summer you can take the Angel's Flight zipline from one to the other. For the less intrepid, a walk among the scattering of Ancient Greek ruins at Metapontum - a 40-minute drive from Matera - can end with a swim in the sea that edges the town.

The beauty of Basilicata lies in a modesty that feels increasingly rare in the current race for luxury - that of a rural culture that has managed to escape the grip of time, despite no longer fitting in. 'Maybe these places are not monumental, like a cathedral,' says Daniele. ‘There is nothing holy, but they should live in silence, with small movements’.

Ways and means

Rooms at Sextantio Le Grotte della Civita (sextantio.it) cost from €214, B&B. Matera is around one hour's drive from Bari airport, which has daily flights from London. The best way to explore Basilicata is by car, travelling the small distances between historic sites such as the torn of Craco, the villages of the Dolomiti Lucane and the beaches.