Douglas Mackie's deeply sophisticated Marylebone flat

It's a touch of the Duchess of Windsor,' comments interior decorator Douglas Mackie, as he sees me looking at the Louis XV-style writing table in his sitting room. The table has the sort of elegant, restrained glamour that Douglas says, with understatement, can be 'quite important in an interior. He makes the Duchess connection because the origin of the desk can be traced to Jansen, the French firm of decorators that numbered Wallis among its prestigious clients in the middle decades of the twentieth century. Jansen frequently used this kind of eighteenth-century furniture in its schemes, in the form of either authentic antiques or superb derivations that emanated from its own workshops (and that are now highly sought-after).

Douglas's writing table, made in the Forties or Fifties, is not the only Jansen piece in his apartment; the huge, lacquered screen in the bedroom is another example of the firm's remarkable craftsmanship. Both pieces were bought by Douglas in Paris, a city that holds a great attraction for him, not least because he finds it a fruitful source of interesting furniture and decorative art. 'I can buy more wonderful things in a single afternoon there than in a whole month in London,' he says. Coincidentally, Paris is also a draw for his partner, Julian Jackson, who is an historian specialising in twentieth-century France.

MAY WE SUGGEST: Interior designer Douglas Mackie's driving tour of the Loire Valley

Their flat is on the first floor of a listed building in Marylebone, constructed in the 1780s. Originally, it would have had fine interior detailing, but by the time Douglas and Julian moved in, two years ago, the only vestige of this was the Adam-style plaster work on the bedroom ceiling. The interior as a whole was bereft of details, so Douglas's first priority was to return a Georgian character to it: Stevensons of Norwich supplied appropriate cornices; Atkey & Company copied joinery mouldings from those in a nearby house of a similar date; and Jamb made the handsome marble chimneypiece for the working fireplace in the sitting room.

While some of the building's previous occupants stripped out original details, others introduced new ideas, including barrel vault ing in the entrance hall. Douglas decided to keep this feature, but he added a small cor nice – with lighting above – and distressed gilding, which together lend grandeur to the comparatively modest space.

With its walls covered in charcoal-grey, paper-backed linen, the hall is a darkly dramatic lead-in to the handsomely proportioned sitting room, which is four metres high and flooded with natural light from the tall windows. Easily combining generous seating and dining areas, it is a welcoming space, with comfortable armchairs and a splendid sofa upholstered in silk velvet. The word 'eclectic' may be overused, but it is difficult to find a better way to describe the room's successfully individualistic - and informed - mix of styles in furniture and art.

Mid-twentieth-century references are very clearly in evidence, with numerous pieces dating from that era, but there are more recent elements, too – many designed by Douglas himself - which sit happily with some much earlier things. For instance, hanging on the wall opposite a large, vivid-green, Sixties painting by Sandra Blow is a seventeenth century Japanese screen-and then, of course, there is the Jansen writing table, its ormolu mounted legs contrasting with the thin, plain outline of a modern, metal console table designed by Douglas, and also with the simple legs of the Fifties armchairs by Terence Robsjohn-Gibbings. Above the dining table, which has a top of American black walnut and a bronze base designed by Douglas, hovers a bronze and mouth-blown-glass chandelier made in the US by Lindsay Adelman.

When I ask Douglas about the thinking behind his choice of such disparate styles and materials, he answers that, ultimately, it comes down to keeping everything-whatever the period – in balance, with scale, form, elegance and finesse being the all-important links. The significance of 'finesse' shows in Douglas's passion for detail, craftsmanship and unusual finishes. He goes to great lengths to track down companies and individuals who understand these concepts and are able to produce work of outstanding quality. The specially commissioned, French-made book case in the sitting room is a perfect example, being realised to Douglas's design in bog oak, brass and, most intriguingly, straw marquetry, a technique with a long history in France but, these days, rarely practised. Other examples are too numerous to mention, but two that are particularly striking are the rug by Hechizoo in the entrance hall, which was woven in leather and copper in Colombia, and the wallpaper in the study, made by SJW Studios in Seattle, using a complex process of folding and hand-glazing.

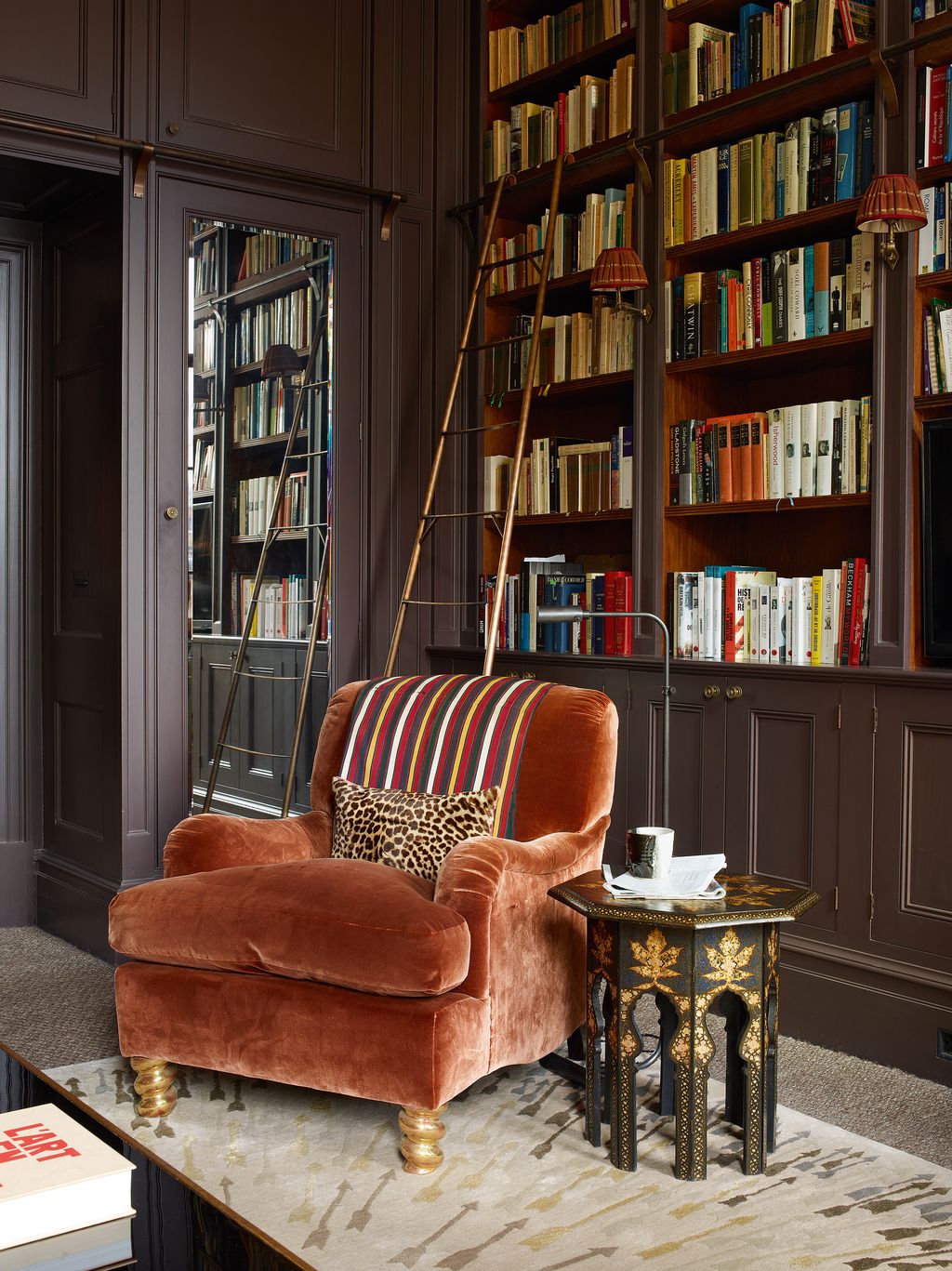

The study is designed to be a ‘working' room, with capacious cupboards and shelves for reference and other books going right up to the ceiling. There is a sliding ladder to access the uppermost areas, but this is as much an object to admire as one to use, for it is beautifully crafted in bronze. However, the study is also a room intended for relaxation and lingering, thanks to the warmly coloured walls, soft seating and cushions covered in antique silk damask - Douglas uses many antique textiles in his schemes - but when, eventually, you can bring yourself to leave, you see, straight ahead of you in the hall, a bold, abstract painting by Adrian Heath. Its positioning directly opposite the study doorway is not accidental – it has been precisely measured to create a 'vista'. Douglas often hangs paintings in this manner, subliminally drawing your eye from one place to another.

MAY WE SUGGEST: Designer Douglas Mackie's country retreat in the Languedoc

Pictures and other artworks mean a great deal to Douglas, and they feature prominently in his home, as they do in most of his projects for clients. Obviously, every commission is different for him, but whether he is working on an urban loft or a country house, in Britain or abroad, he always likes to think of the decorating as a symbiotic process, in which, ideally, art and furnishings are considered simultaneously. Although he studied architecture at university, he soon realised that he wanted to practise in a broader context, which would allow him to combine this discipline with his love of art, furniture, textiles and colour. That longing led him, very successfully, to the all-encompassing world of interior decoration.