A Maine barn decorated with natural materials from its rural surroundings

Connected farm buildings began to appear all over rural New England in the nineteenth century, not, as is commonly believed, for protection on the trek from big house to barn during the region’s frigid winters. The arrangements grew out of Yankee practicality, set up for the mix of industry that took place there: growing crops, raising animals, and making crafts and clothing.

How fitting, then, that photographer and lighting designer Chris Baker and his wife, Odette Heideman, a literary editor and ceramicist, fell for an 1850s Cape and its attachments while visiting a friend Down East several summers ago. Not that tending crops and cows was part of the plan, but producing and creating has long been in their DNA.

“Our goal is to make as many of the things that we live with as possible,” says Baker, whose delicate curtain rods, light fixtures, and built-in shelving pro-vide the armature for handmade linens and Heideman’s pottery collections. Every room, each one dedicated to a single purpose—eating, reading, sleeping—is a reflection of the couple’s aim. A sophisticated mix of paintings and photographs, textiles, lighting, and objects mingle with modern and antique furnishings, tricking even the most astute into thinking that the couple, parents to two grown daughters, have lived in this place forever.

MAY WE SUGGEST: A charming cottage set amongst the lush landscape of North Carolina

This is the home of artists who see creative possibility and utility everywhere. For Baker, who studied botany, the seven-acre field behind the house provides endless natural curiosities that have become the subject of his photographs. Dying maple and pine trees yielded firewood that he stacked Scandinavian-style into a sculptural beehive. Heideman has searched out Maine granite chips to incorporate into the Japanese-style clays she uses, and she mixes granite dust into her glazes, some made from the pine and maple ash on their land. Morning walks yield seaweed that she boils to make funori, a gel-like substance used to render slips more brushable. They’ve even planted red-stemmed willow from which to make teapot handles.

Their surroundings have provided the pair with much, but both Baker and Heideman agree that it is the big house, little house, back house, and especially the barn as work space that brought them to this place, far more remote—and expansive—than their prior home on Long Island’s East End. Says Baker, “Moving into this home gave us not only the space but the permission to do what we really want to do. Everything else is the cream on top.”

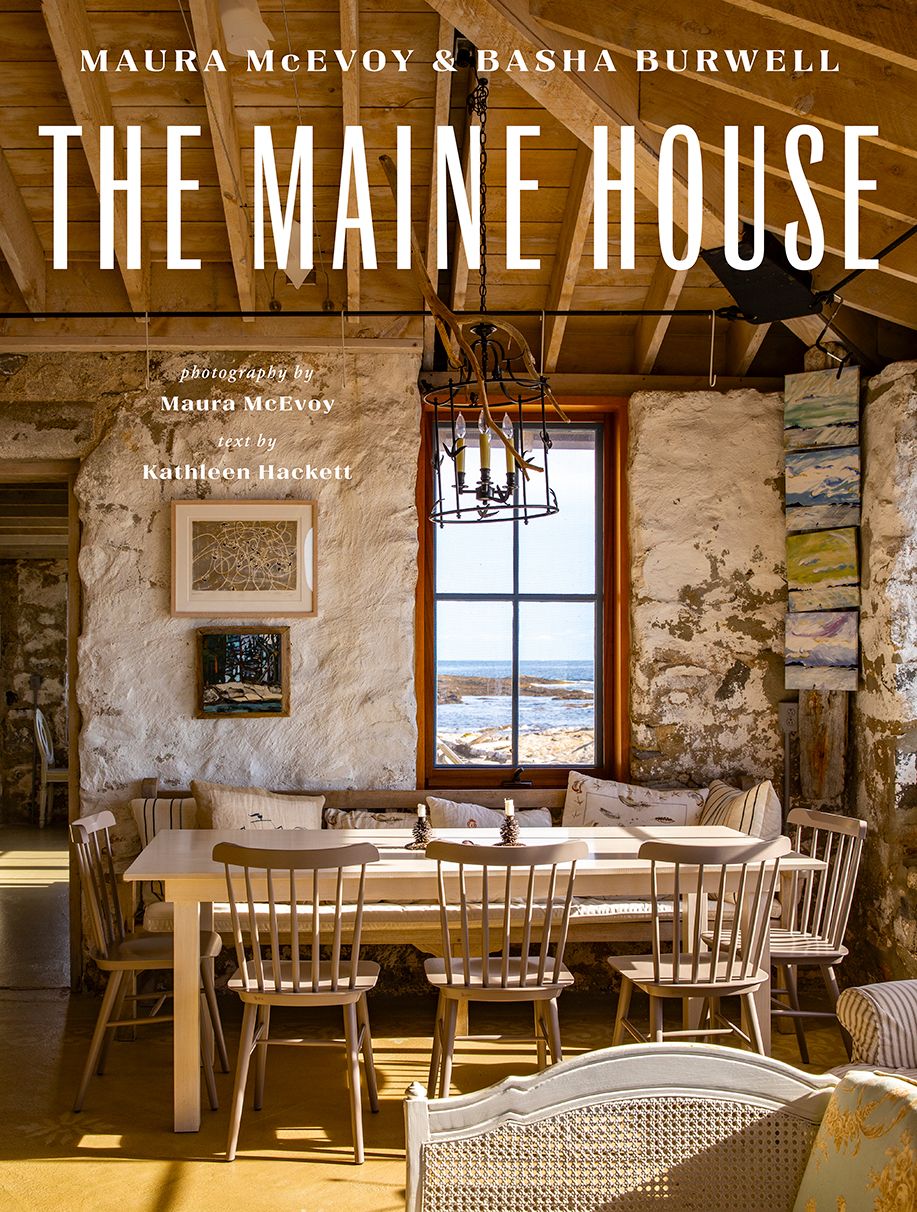

This is an extract from The Maine House by Maura McEvoy and Basha Burwell, text by Kathleen Hackett. Published by Vendome Press.

MAY WE SUGGEST: A fantasyland in the Hamptons by architect Pietro Cicognani