Our familiar Christmas treats have evolved over time, some significantly in the past 100 years. The mince pie is an icon of the British Christmas. Modern consumers wrinkle their noses when they learn the original mince pie also contained shredded meat. Isabella Beeton, author of Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, included beef, as well as dried fruits and spices, in her 19th-century recipe. These expensive ingredients denoted mince pies as celebratory fare eaten at feasts all year round.

That other festive favourite, Christmas pudding, began life as a thick, spiced porridge-like substance known as plum pottage. It also included meat or at least a meat-based stock, breadcrumbs, and dried fruit, collectively known as plums. The plum pudding we recognise today emerged in the 17th century. A more solid affair, it contained similar ingredients to the pottage, but was boiled in a cloth to produce the ‘speckled cannon-ball’ dessert presented by Mrs Cratchit to her family in A Christmas Carol.

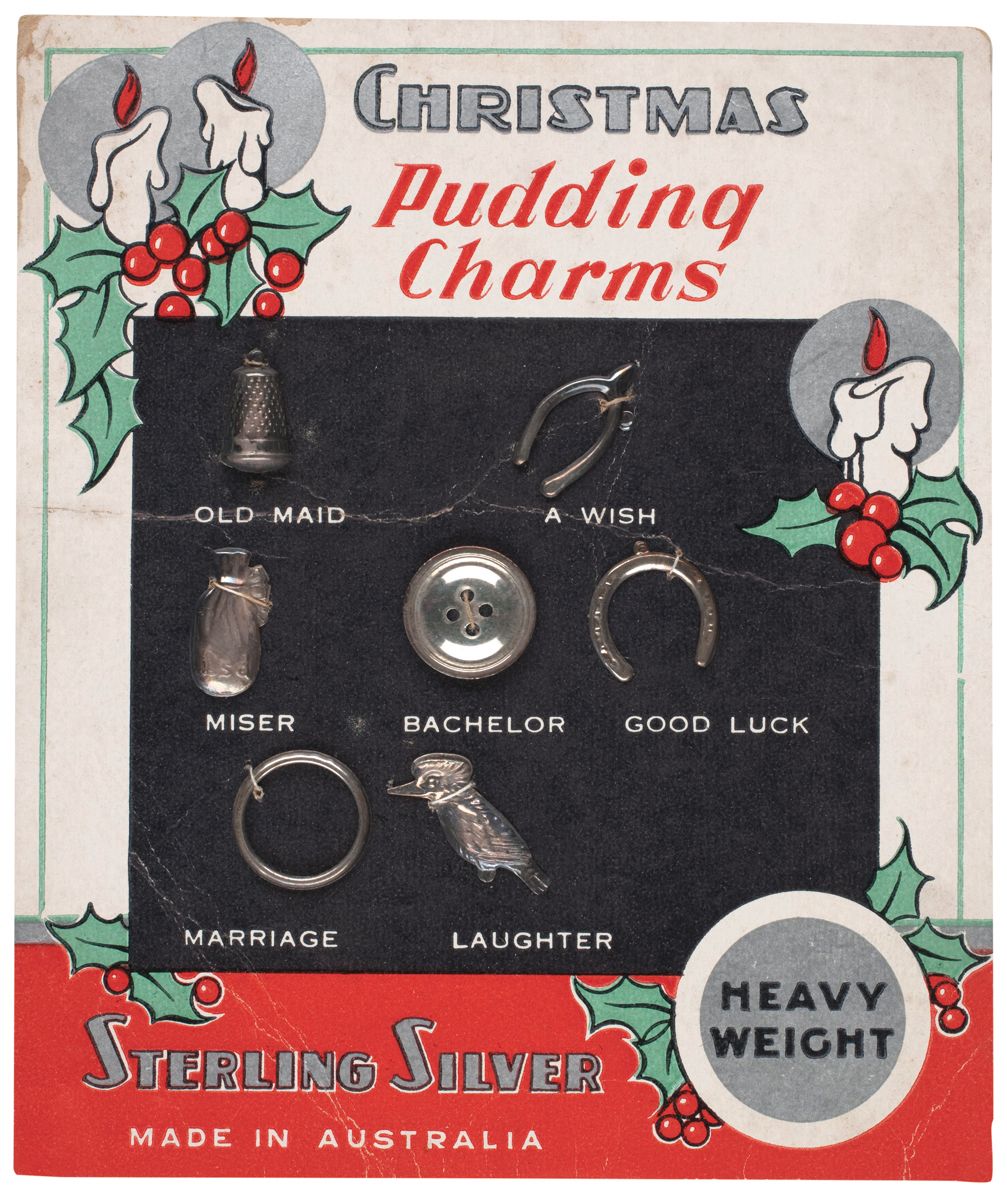

By the mid 19th century, plum pudding was indelibly linked with the festive period, with English food writers referring to it as Christmas pudding rather than by its original title. The Victorians were also responsible for bigging up the mythology around the pudding. It was they who popularised the idea of Stir Up Sunday and suggested including charms to foretell the recipient’s future for the coming year.

MAY WE SUGGEST: All the best Christmas dinner recipe ideas

Plum pottage is now a relic of the past in Britain, however, in Scandinavia, a rice porridge or pudding is still served. It is crucial to leave a bowl out for the jultomte, or elves, to thank them for taking care of the house and animals over the previous months. The Swedish appreciate the importance of pacing yourself when feasting. Their festive julbord or smorgasbord is designed to be enjoyed over several hours with small servings of each dish, including pickled herrings washed down with aquavit, cured meats and liver pâté, and hot meatballs and ham, with a variety of side dishes and breads.

The turkey appeared in Britain in the early 16th century, many arriving from the Americas via Turkey (hence the name). By 1573, turkey was listed alongside capon and goose as ideal Christmas fare. Other nations have resisted the turkey onslaught. In Germany, goose with apples remains popular. Although Japan does not officially celebrate Christmas, it has become the custom to eat Kentucky Fried Chicken on the day.

The festive fare barrage begins long before we sit down to Christmas dinner. Shortly after Halloween, the shops begin to fill with Christmas treats. In Great Britain, chocolate boxes jostle for attention with mince pies and biscuits. Gingerbread gets a European makeover with German lebkuchen, Norwegian pepperkaker, and Dutch speculaas. These have largely ousted regional British Christmas specialties, such as Yorkshire pepper cake, traditionally eaten with Wensleydale cheese.

Many cakes were originally destined to be eaten on Twelfth Night. In France, they commemorate the visit of the three kings with a galette de rois, a buttery pastry dome filled with almond paste. New Orleans has its king cake decorated with green, purple and gold sugar sprinkles. The Italians have their statuesque panettone laden with dried fruits. It used to be traditional to keep a little until February 3, the Feast of San Biagio – believed to cure sore throats and colds – when the leftover panettone was eaten for breakfast to ward off winter chills.

The British Christmas cake has evolved from its own version of a king cake. In the 17th century, twelfth cake was a spiced, brioche-like dough with dried fruit that contained a single dried bean. If you found the bean, you were crowned king for the evening’s festivities. As the years passed, the custom of using a cake to select a ‘bean king’ waned and the mixture itself became the dense fruit cake covered in marzipan and icing now associated with Christmas. In the early 19th century, ostentatious twelfth cakes adorned many a baker’s window. However, as Queen Victoria’s reign progressed, it became customary to make your Christmas cake at home. The twelfth cake effectively morphed into the Christmas cake and it became another relic of Christmas past, much like the plum pottage.

By Epiphany, most of this Christmas fare has been consumed. With slightly expanded waistlines our minds turn to a more restrained form of eating. Most of us will have over indulged but, after all, it is Christmas, and it only comes once a year.

This is an edited extract from The Christmas Book by Phaidon Editors with essays by Sam Bilton, Dolph Gotelli and David Trigg, published by Phaidon