The history of any nation could be easily traced from the design of its furniture. Sudden changes in ways of life, revolutions, violent or peaceful, the acquisition of new empires, great wars in distant places, the appearance of a striking new personality on the social scene, as well as the sudden changes of fashion at home, are reflected, as through a reducing glass, in the design and construction of the objects of everyday life.

In the second half of the 17th century, English explorers and navigators lost their lives in attempting to establish trading positions in the remote and fabulous East; soon afterwards, Chinese porcelain made its appearance on the tea-tables and dressers of plump housewives in Cheapside. Great adventurers, both Spanish and English, disappointed in their search for gold in the West Indies, filled their returning ships with a ballast of mahogany, which was plentiful there and considered of little value by the natives. Within a few years, mahogany, with its outstanding qualities for furniture-making, was to be met with in many forms in every Englishman's home; feathers and ears of wheat, so often used by Hepplewhite as carved ornaments to his chair-backs, seem to symbolize the Prince of Wales' leadership of fashionable London and the rich acres on which the fortunes of the landowners depended. Towards the end of the century, Frenchmen from Brittany or the Midi were killed fighting Bonaparte's war in the shades of the Pyramids, and before long the Sphinx smiled enigmatically from every smart Frenchwoman's writing desk. As the 19th century dawned, and before the smoke of gunfire cleared from the sea off Spain, Jane Austen's Emma Woodhouse, in white muslin, was watering her plants on a balcony named after Trafalgar.

In the next pages is a series of sketches, arranged in periods of half a century, to show how design in furniture has changed with historical events, from 1650, when Cromwell and the Commonwealth were ruling England, until the early 19th century, when Victoria's long reign had already begun. Few pieces of furniture made before 1650 are now available to the general collector, and furniture of the Victorian era made after 1850 can, as yet, hardly be regarded as "period furniture" in the antique sense. So we have confined our examples to those two epoch-making centuries in furniture, 1650-1850.

We hope that the drawings will act as a guide to those who would like to start collecting old furniture, to actual owners of antique pieces who may wish to know their possessions better, and last, but not least, to those who intend to possess fine contemporary furniture-the antiques of the future-but who realize that it is sounder to know something about its predecessors, and its derivation.

1650-1700

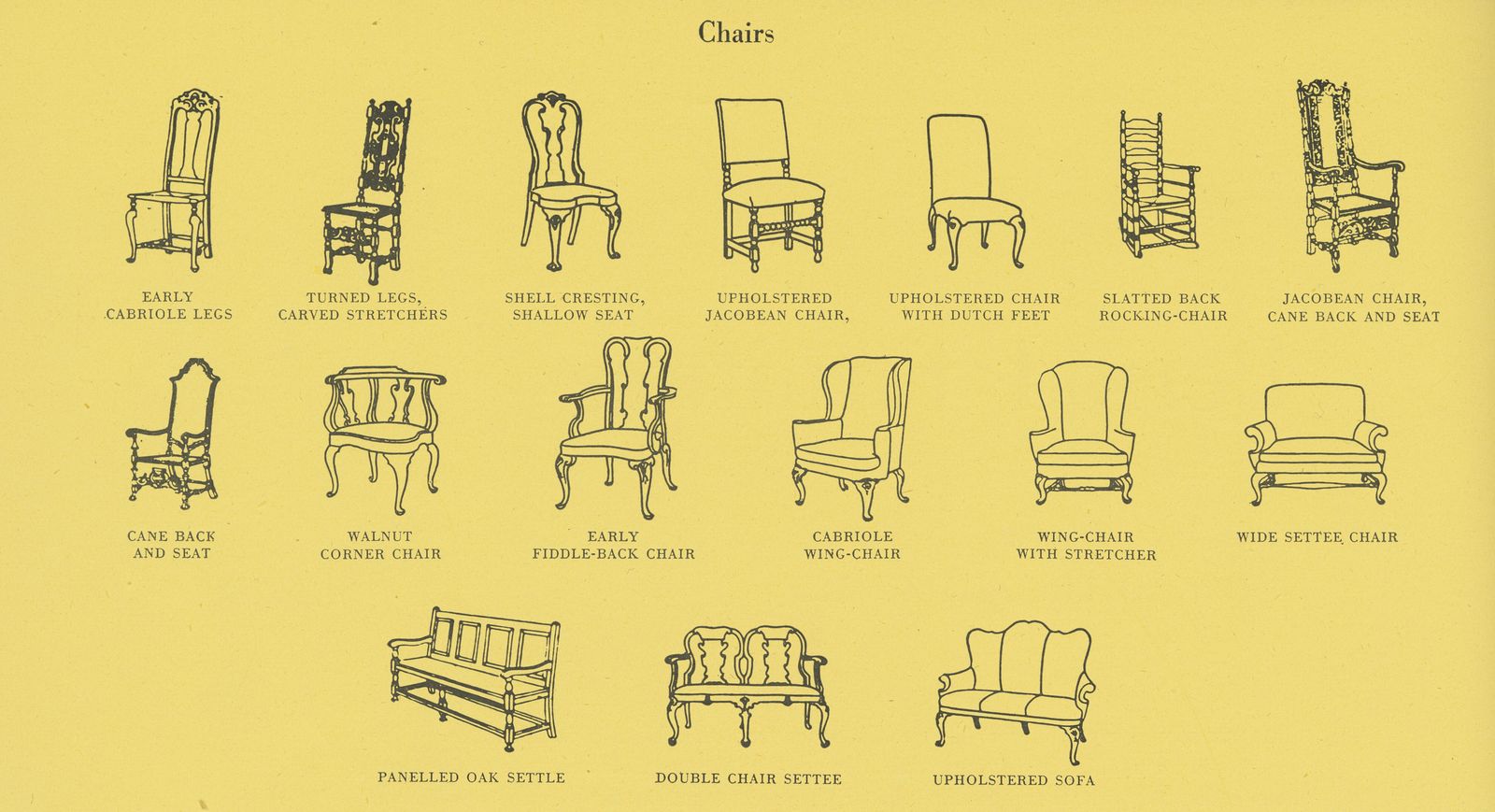

At the turn of the 17th century, England lay in the grasp of the Puritans, and the stern, simple manners of the Protectorate were coldly reflected in the furniture of the period. Chairs with uncomplicated carving, and refectory and gate-legged tables, usually made of oak, were distinctive pieces of the time. Some mild elaboration in the form of turned legs to chairs and tables was allowed, and it was under Cromwell that the then-daring "barley sugar" turning was finally evolved.

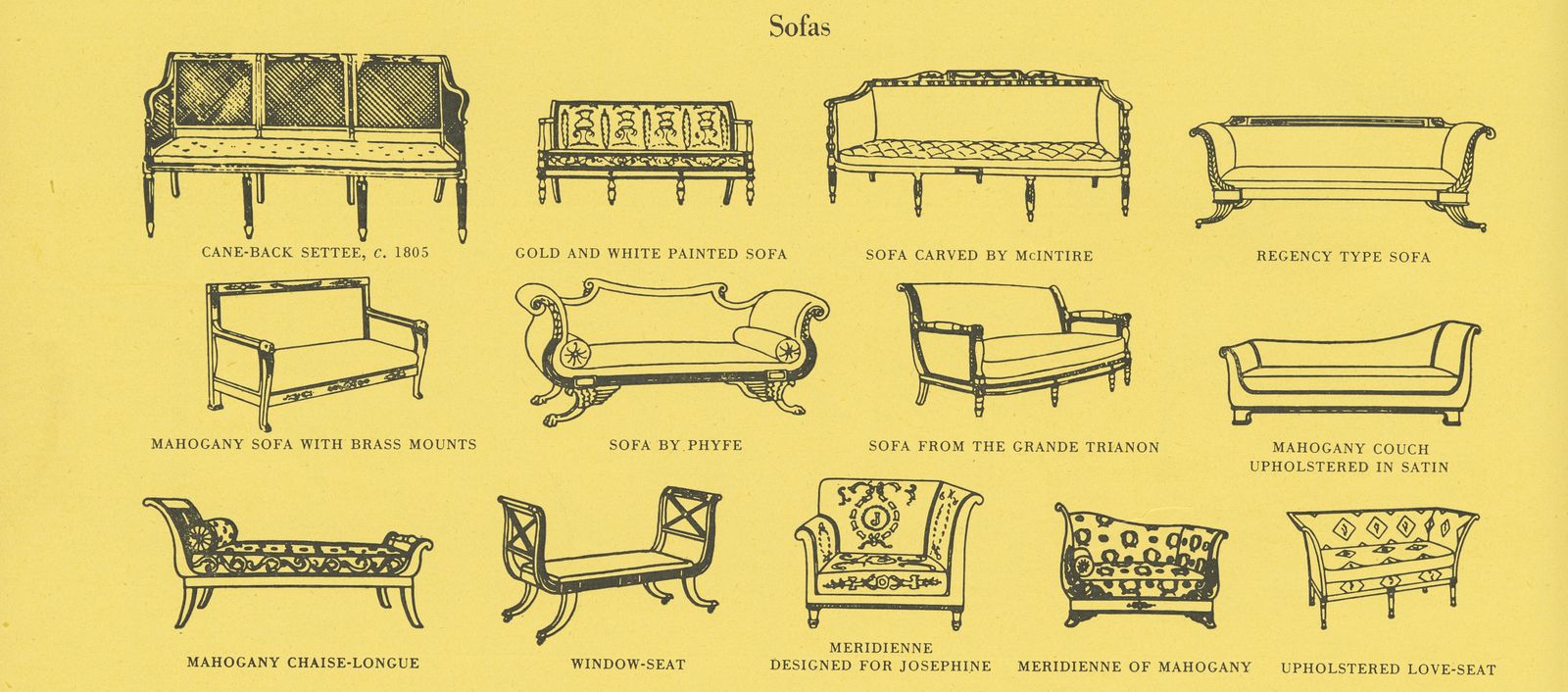

Chairs grew in number, but stools continued, and with turned legs and stretchers they were extended into fireside benches. From 1660, Charles II influenced the return to the elaborateness of the Elizabethan times. Luxury, which had been forbidden for so long, became the craze, and chairs and sofas were opulently upholstered in brilliantly coloured brocade and velvet. Love was in the air, and for elegant dalliance the love seat, a sofa for two but no more, was invented.

Courtiers and leaders of fashion, long in exile, introduced to England the taste for different woods, and ladies wrote invitations to secret supper parties at lacquered or walnut secretaries. The new woods-walnut especially-could be carved against the grain, and this allowed craftsmen greater freedom in their chair designs, which rapidly became more elaborate, and were soon backed and seated with rattan-cane, newly introduced from the East. Examples of the furniture of this period are not only admirably displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum, but even more effectively at Ham House, near London, now open to the public. Ham House was redecorated and furnished in the richest Restoration style by the Duchess of Lauderdale.

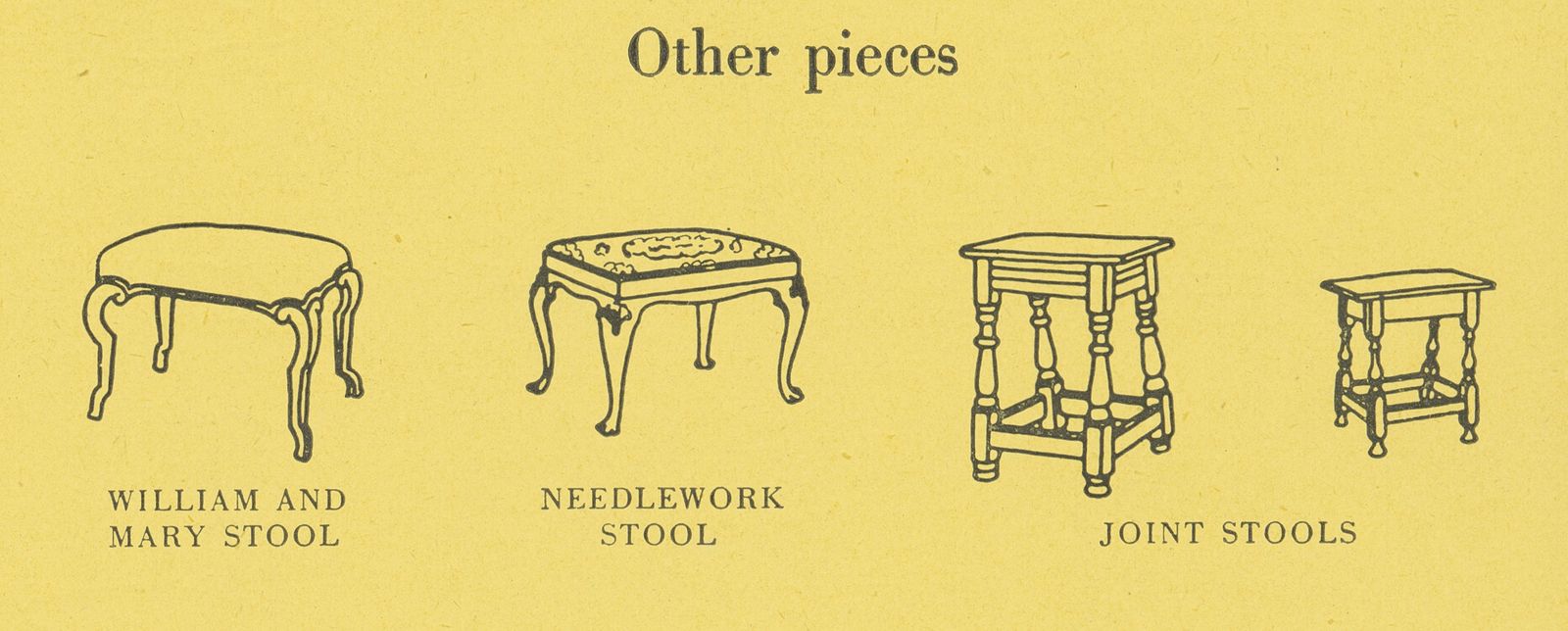

A more sober note was struck after the death of Charles II, during the short and troubled reign of his brother James. In 1689, William III replaced James on the throne, and he and Queen Mary gave their names to a style which shows a strong Dutch influence. Holland had long traded with the Far East, and at about this time oriental porcelain was first introduced in large quantities into England. Characteristic of the William and Mary period in furniture was its solid Dutch construction, enlivened only by some elaboration in the stretchers and legs of tallboys and occasional tables.

Some connoisseurs regard the William and Mary and Queen Anne periods as the golden age of English furniture, for pieces were beautifully and simply designed, and achieved their rich effect by the skilful use of veneers and inlays rather than by the baroque curves of twenty years earlier. At this time fine furniture began to be bought by merchants and farmers, who, up to then, had lived in the simplest way. The Windsor chair, still popular today, was made in the well-wooded districts of Buckinghamshire and made its first appearance even in cottage homes.

1700-1750

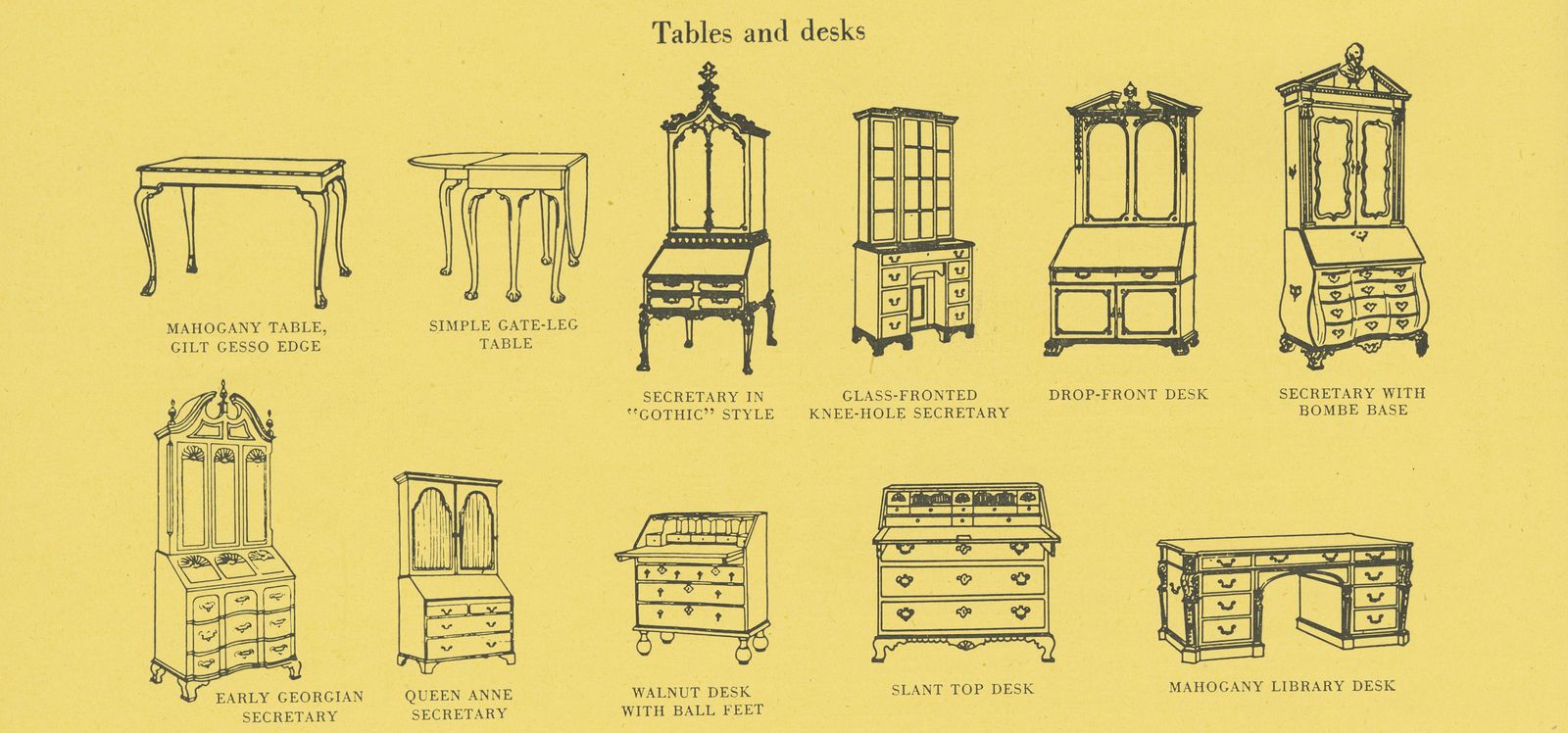

Queen Anne's accession almost coincided with the start of the new century, and the peace won for her by the Duke of Marlborough's famous series of victories on the Continent gave great opportunity for the domestic crafts to flourish. Her reign, and that of her successor George I, covered a most important period of English furniture making, starting with the walnut age, and ending in the hey-day of Chippendale's daring use of mahogany.

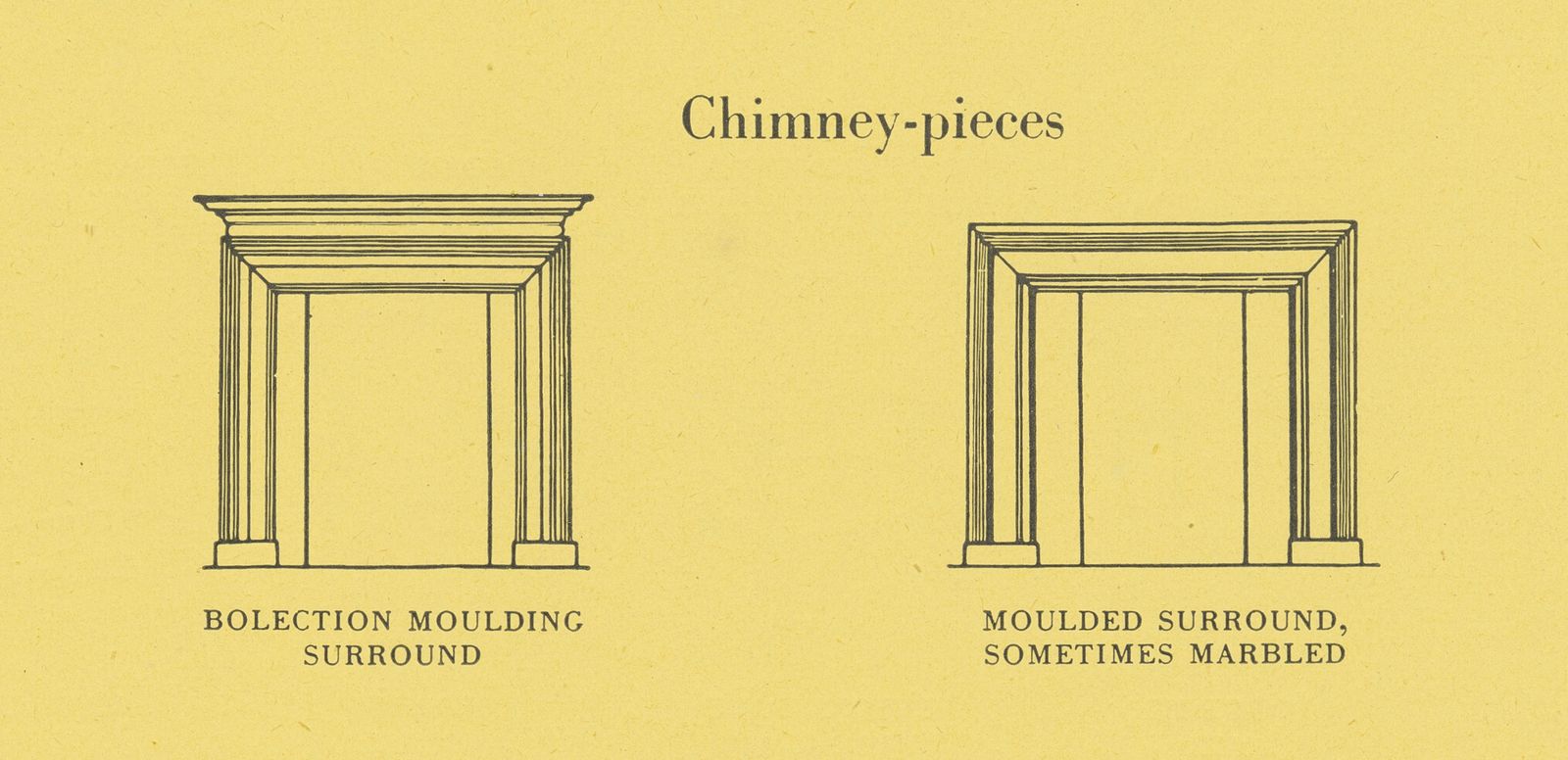

The "small Queen Anne House", with its neatly panelled rooms and simple, yet in its way perfect, furniture, first appeared at this time, though most of such houses were built a little later. Anne and her Danish husband were comfortable folk and the furniture of their time was comfortable, too. The Queen Anne style formed the link between the heavy underbracing of the preceding periods, and the delicate style of the late Georgian designers, notably Hepplewhite and Sheraton.

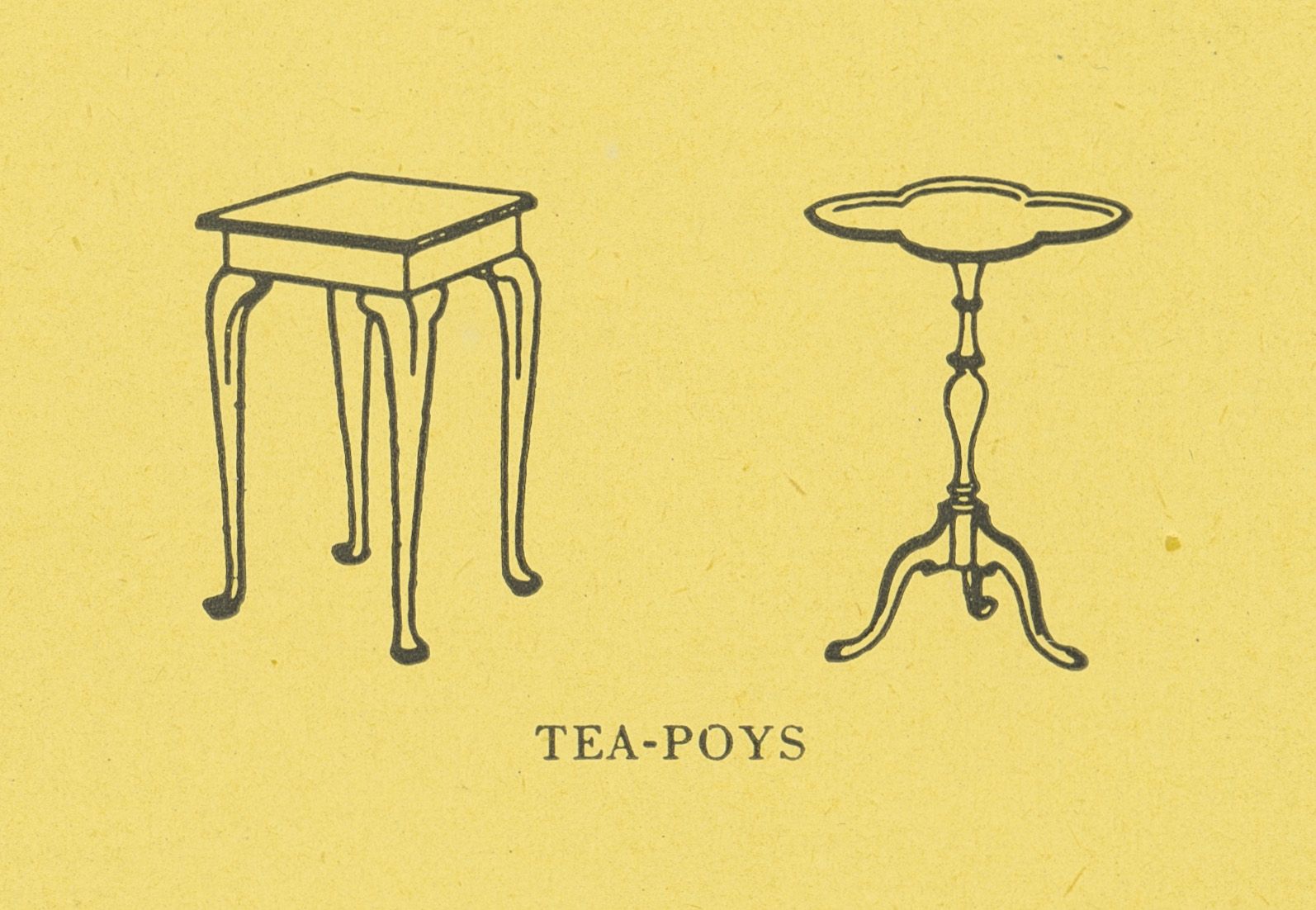

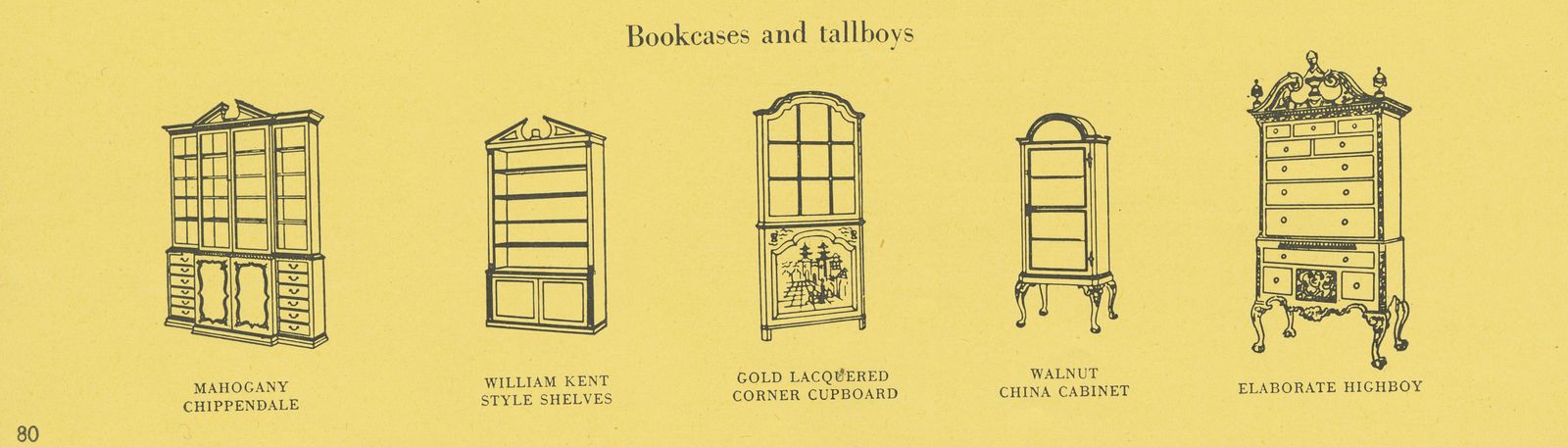

Though stretchers, varying from preceding forms by being recessed between the front legs, were employed at first, they later disappeared altogether. Lacquer was still imported from the Orient, and counterfeited (not very successfully) at home. Marquetry was frequently used and Dutch flower and fruit designs were adapted and refined by English craftsmen. But the glory of the period was the beauty of the walnut wood, generally used either alone, or with inlay, or set off with gilding. The cabriole leg was the outstanding detail, often having the knee carved with a cockle-shell design, a favourite ornament. The claw and ball foot came in during this period.

In 1715, a new wood quickly became the most popular for furniture-making. This was mahogany, first imported as ballast into England from the West Indies, by chance, but quickly noticed by craftsmen for its unique strength, close-grain, and ability to take high polish. In the first half of the century the wood was used sparingly by such craftsmen as William Kent, who specialized in furniture which was heavily gilded; the tables, with their lion masks and heavily swagged decorations, were often surmounted with marble tops.

Kent's furniture was essentially suited to the houses of the aristocracy, and by the time of his death, in 1748, the way was clear for the smaller, more practical pieces by a group of new craftsmen, headed by world-famous Thomas Chippendale. Chippendale, born in 1718, was at first strongly influenced by the growing interest in the Continental rococo style, but did not publish his famous Director until 1754. Though the more elaborate ornamentation of the Louis XV rococo style never found great favour in England, Chippendale, nevertheless, designed some distinctly rococo pieces, and also indulged in several other flights of fancy-tables and chairs with Gothic and Chinese idioms, or chairs with seats and backs like giant sea shells.

1750-1800

In 1750 England entered a period when growing prosperity at home and increasing trade abroad enabled her to survive the war which lost her an American empire. Not only did she survive, but such was her growing vitality that a few years later she was able to face and finally conquer Napoleon. At home, wealth was no longer confined to a few aristocratic families living on vast estates. All over England smaller country houses were being built, and a number of craftsmen, whose names are now famous, were there to design their furniture.

After Chippendale (1718-1779) came Hepplewhite (1765-1786), who was strongly influenced by the French furniture of Louis XVI's reign, and whose earlier pieces were exquisitely curved and graceful. He aimed, to use his own words, at" uniting elegance with utility". Furniture inspired by Hepplewhite is easily recognized and is to be found in many English homes. Chairs had backs that were nearly always open and very rarely upholstered. They were seldom square, but shaped· like shields or interlacing hearts, with a central splat ornamented with ears of wheat or Prince of Wales' feathers. Legs were often fluted and tapered. Furniture in satinwood, its beautiful surface further enriched with painted miniatures is also attributed to Hepplewhite, who evolved the sideboard as a separate piece of furniture.

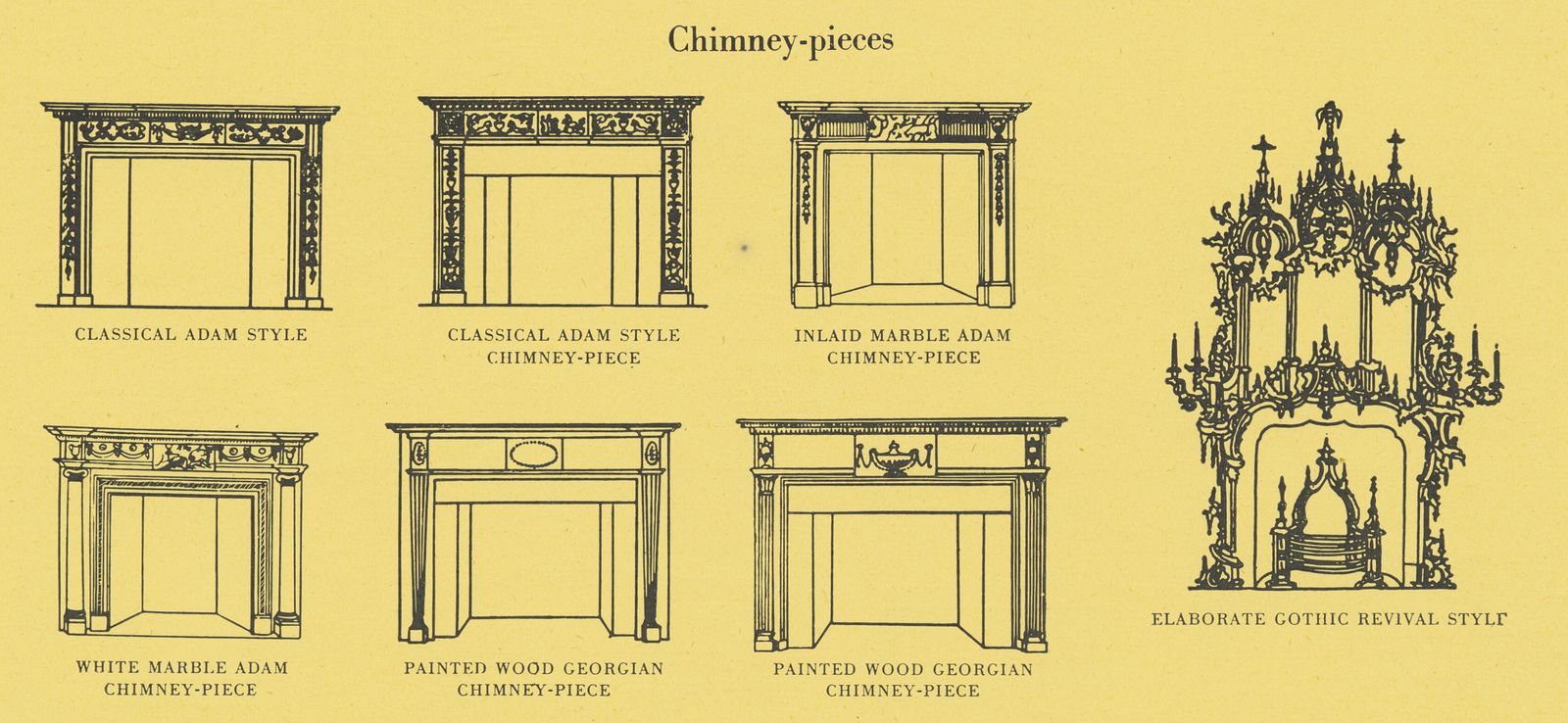

The Adam brothers, who left their native Edinburgh soon after the turn of the century to design palaces for the English, further filled them with magnificent furniture of their own design, or which was designed especially for them by other masters of the day. But they were also the architects of blocks and terraces of smaller houses, the most famous being Adelphi (" the brothers"), now largely destroyed, but which in its time was the inspiration of thousands of modest but perfectly proportioned house-fronts all over England, each with its symmetrical fenestration and fanlighted front door. The Adams, in their design both of houses and furniture, contrived to transfer to their work" the beautiful spirit of antiquity", but their Scotch good sense enabled them always to remain well within the British tradition of good design and suitability.

But it is Sheraton, perhaps, whose work most typifies the furniture of this half-century. Born in 1751, he delighted in simpler and straighter lines than Hepplewhite, and was the champion of the use of rare and beautiful woods, such as satinwood and amboyna, enriched with inlays of ebony, ivory and brass. His chairbacks were often square, but with straight top rails, unlike Hepplewhite's which were curved and which, instead of a splat, bore a panel in the form of a vase or lyre. Of particular interest in Sheraton's work are his designs for ingenious folding beds, and couches that became tables, in parlours which had to serve as bedrooms at night.

1800 onward: the Regency and beyond

The dawn of the new century, a century which was to see the decline of craftsman-designed furniture and the triumph of the machine age, found England in the throes of a deadly war, a war in which Bonaparte achieved a petty triumph he had never sought: for English craftsmen adopted as their own the very emblems of the French victories. Following the Egyptian campaign, sphinxes made their appearance as decorative motifs on English furniture--not the seductive, smiling sphinxes with pearl-looped bosoms and Marie Antoinette hair-styles of a slightly earlier period, but forbidding, half-women, stern daughters of a cold and imperial classicism. The eagle, the star, the victor's laurel wreath, the palm, and even the crocodile, became the exotic emblems with which the early 19th century adorned its furniture, and which, combined with emblems betokening English victories, lions' feet on "Trafalgar" chairs, and dolphins, are now the hall-marks of the period which we loosely call "Regency".

The Prince of Wales became Regent in 1810, though "Regency" furniture–"Trafalgar" chairs, for instance-was being made a few years before. In France much the same style prevailed, though a British blockade prevented imports of mahogany and caused French cabinet-makers to resort to native woods-rosewood or fruit woods, and to more gilding and Fainting. As befitted a new Empire, designs had to be suitably splendid, and Percier and Fontaine, designers to the new court of Napoleon and Josephine, created pieces which, though magnificent, were too massive, and lacked the elegance and good taste of the Louis XVI and Directoire periods.

In England, Thomas Hope took much of his decorative detdl from across the Chmnel, but his furniture designs owe much to the ancirnt Greeks, while preserving a British character of their own. His book, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration, published in 1807, had great influence, and his neo-classic designs inspired a host of lesser craftsmen to create furniture in such quantity that it is still to be found and bought at reasonable prices all over the country today. Regency furniture, until recently dismissed by most connoisseurs as "English Empire", is enjoying great popularity today.

The Regency period was followed closely by the long Victorian age, which in its first few years produced isolated examples of attractive furniture, usually more pretty than practical, for example the papier mache chair, but was soon to flood the market with mass-produced pieces, most of which were too large, heavy, cumbersome and clumsy, or cluttered with meaningless ornament.