From the archive: the joys of vicarages (1966)

Vicarages are full of comfortable associations-vicarage teas, church fetes, vicarage lawn croquet-and this cannot just be because they seem part of a peculiarly comfortable way of life. It must be partly because vicarages themselves are rather comfortable houses. The vicar has in so many places been the next most important person after the squire, and so his house is often the best kind of 'middling' house: larger than a farmhouse, smaller than the seats of the gentry, a pleasant, livable-in kind of house in a social and architectural scale of its own.

Few houses of any kind remain from the Middle Ages, and so, naturally, do few vicarages. Most of those which have survived are fairly grand, such as the one at Ashleworth in Gloucestershire (black and white), at Elsdon in Northumberland (fortified against the Scots), at Hadleigh in Suffolk (a romantic tower), or at Kentisbeare in Devonshire (which can be visited by writing to the owner).

But in the Middle Ages there were many more priests than latterly, and all of them bachelors (at least nominally),and many of them must have lived in hovels like the peasants, or inside their churches. As late as 1819 the vicar of Fulstow in Lincolnshire accompanied an application to build a new vicarage with a sketch of his old one which may well have been medieval: all it must have had was two rooms with a chimney stack between them.

Little was done by way of vicarage building in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This was a time when the church was always in some danger, real or imagined, from Catholics or Puritans, and nobody can have been very keen to spend a lot money on a house that he might be turned out of next month. Not every parson was as flexible as the vicar of Bray, and mostly the medieval parsonage was built simply to serve.

Christopher Wren, the great architect of a new age, was born in the medieval rectory at East Knoyle in Wiltshire in 1632. The turbulence of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries gave way in the end to the calm of the eighteenth, when to any thinking Englishman the British Constitution and the Anglican religion seemed the best in the world, and the parson in his parsonage a natural part of the settled order of things.

The best Georgian vicarages are like the ideal of a parson poet, the Reverend John Pomfret, who wrote, about 1700, of his perfect house: 'Near some small town I'd have a private seat, built uniform not little, not too great'. His rectory was Elizabethan, but there are hundreds of Georgian vicarages just like his, with unassuming four-square façades, dignified but friendly.

Occasionally they may have been designed by a leading architect. Woodstock, standing at the gates of Blenheim Park, must be by Vanbrugh, though there is nothing to prove it; it has all his hallmarks: heavy keystones, huge brackets to support a cornice and pediment, and great pilasters at the corners. Bradwell Lodge in Essex had additions, perhaps by Robert Adam, for a fire-eating parson journalist, the Reverend Henry Bate Dudley. Tom Driberg, a sometime fire-eating MP journalist, lives there now, and shows it to the public. Saxlingham in Norfolk, from the end of the century, is by Soane, and has the bowed centre and central attic that he so often uses. Yaxham, also in Norfolk, of 1822 but still 'Georgian' in feel, is by Lugar, who called it 'a very comfortable retired residence'.

But most of these vicarages are quite anonymous, built by local architect-builders who, with the aid of pattern-books and rules-of-thumb, could produce just the kind of handsome, small-large house that was needed.

These vicarages display the social status of the vicar who lived in them - a position that comes out best in Jane Austen. She was a parson's daughter, and her family moved freely on the edges of 'county' society. Edmund in Mansfield Park and Henry Tilney in Northanger Abbey must be typical of very many clergymen - the younger sons of good families, moving as easily in the ballrooms of Bath and in the hunting-field as in their parishes, and finally provided with a living and a vicarage that would not disgrace them. Henry Tilney's parsonage was 'a new-built, substantial stone house, with its semi-circular sweep and green gates'. 'We are not considering it a good house,' said General Tilney, 'we are considering it a mere parsonage, but decent, perhaps, and habitable.'

Of course, there was another side of things. While many parishes were well-endowed and well-looked-after, many more were in the hands of absentees, and there must have been of poor clergymen like Parson Adams in Fielding's Joseph Andrews or like Goldsmith's in The Deserted Village, who was 'passing rich on forty pounds a year.'

But this is social history, not architecture. These parsons lived in cottages like their villagers, even boarded in the pub, and they left no good houses, as richer parsons did.

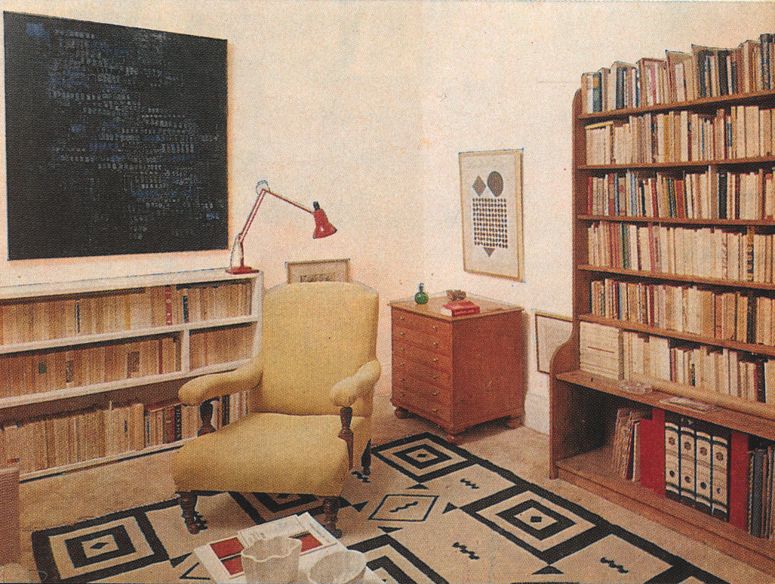

Vicarages often reflect the interests or eccentricities of past vicars. Most decent vicarages have a library (the word 'study' is a vicarage usage), but the vicar of Goodmanham in Yorkshire must have been a scholar who couldn't spell; one of his cases is labelled 'Naturel History'. Eynsham, in Oxfordshire must have had an antiquarian vicar: alongside the pleasant vicarage is a sort of folly-archway built of fragments from a ruined abbey. Berkeley, Gloucestershire, has a charming, rustic summerhouse at the bottom of the garden, where the vicar's son, Dr Jenner, made his first experiments with vaccination.

R S Hawker, vicar of Morwenstow in Cornwall and composer of 'And shall Trelawny die', decorated his vicarage chimneys with models of all the churches he had been connected with–except that he had one chimney too many, and that he capped with a model of his dead mother's tomb. Sydney Smith, the great clerical wit, actually built his own parsonage at Foston in Yorkshire with his own (and his wife's) hands. It can be visited on Sunday afternoons.

And, as the century went on, these Gothic vicarages got larger, gloomier and more numerous. 'It ought to be distinctly religious in its character and stand in protest against the luxury and worldliness of modern domestic buildings.' Some vicarages, built on this excellent advice, and now empty of the hugeVictorian families they were intended for, their narrow windows half-blocked by a century of suffocating evergreens, and infused with smells of the drains and schoolroom cabbage of a hundred years ago, are very unluxurious indeed.

But still the Good Life (sometimes without a capital G) was led within them, and many vicarages (like Trollope's Plumstead Episcopi, where Archdeacon Grantley lived) were models of opulent sobriety, where in everything 'the apparent object had been to spend money without obtaining brilliancy or splendour'. Perhaps the best illustration of the inside of such a parsonage is the original cartoon of the Curate's Egg.

It was the heyday of the squarson. Archbishop Benson, first Bishop of Truro, was introduced to the breed when staying in a Cornish rectory for the weekend. Last thing on Saturday night the butler came up with the cellar book, and asked his master 'Will it be claret or burgundy for Communion tomorrow, sir?' 'Oh, I don't know,' said the squarson, 'try 'em with hock a change.'

In Hampton Lucy in Warwickshire, the parson kept a notable table, and often the maids in the big house, drawing the curtains in the early morning, would see the lights of the vicarage across the park still burning in the dawn, as dinner guests sat talking over their port.

Many vicarages, in fact, preserved an eighteenth-century air about them, and only at the end of the century were most vicarages invaded by the terrible public-school stuffiness that Osbert Lancaster has caught so brilliantly.

In this century there has been far less vicarage building, and many have in fact been sold (including some mentioned in this article) as too big and unmanageable on present-day clerical stipends. Many of those that have been built recently have been somewhat unimaginative (though a notable exception is the new vicarage at Deptford). This is perhaps inevitable, partly financially and partly because of the modern appraisal of the social role of the church; a parson should not live apart from his parishioners.

But the best vicarages are still those like Trollope's Framley, 'a pleasant country place, having about it nothing of seigniorial dignity or grandeur, but possessing everything necessary for the comfort of country life ... and all the details requisite for the house of a moderate gentleman of moderate means', and there are plenty of moderate gentlemen these days who find old vicarages ideally suited to their ideas of living.